The Art Blockbuster: The Greek Miracle.

Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy - The Fifth Century BC

The exhibition The Greek Miracle. Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy. The Fifth Century BC was displayed at the National Gallery of America in Washington DC from 22 November 1992 to 7 February 1993 and then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from 11 March to 23 May 1993. The exhibition marked the 2,500th anniversary of Kleisthenes' reforms of the Athenian constitution in 507/8 BCE, which, it is argued, marked a change in political practice and led to democracy in Athens. The Greek Miracle at these two American venues displayed art from the time of Kleisthenes' reforms to the late fifth century BCE in an attempt to illustrate how art in Athens (and to some extent Greece in general) developed over this century. The exhibition continued the story of Greek art through the Greek classical style from the development of archaic art through to early classical style that had been displayed in The Human Figure in Early Greek Art exhibition that had been held at the National Gallery of Art in 1988. This earlier exhibition had then toured a number of other venues in America until September 1989.

The two American venues hosting the show are defined as art museums, though the Metropolitan has a large and significant archaeological collection, and the objects were aesthetically displayed as art objects. It was the first time that Greece had ever loaned many of its most important objects to an international exhibition and the exhibition also included loans from the British Museum in London, the Musée du Louvre in Paris and other European museums. The exhibition was significant for a number of reasons: it was a major ‘blockbuster' of classical art for a broad general public; it included a huge international loan from Greece (which also entailed the loan of major art works from the two American venues to the National Gallery in Athens); the visual marking of the ‘birth of democracy' through an art exhibition; the publicity around the exhibition and its announcement; the political involvement of the Prime Minister in Greece and President of the United States; the timing of the exhibition in 1992-3; and the critical controversy (and indeed hostility) that the exhibition caused.

The Lenders and the Objects

The most important thing about any exhibition is the objects on display, though interpretation and presentation influence how these objects are received. Every object chosen presents a choice on the part of the curator (or curatorial team), lending institutions and hosting venues. Therefore it is important to consider what was displayed, from where and why certain ‘key' objects were chosen for The Greek Miracle. Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy. The Fifth Century BC.

The objects came from a great number of institutions in Greece and the rest of Europe as well as from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York itself. The institutions that lent objects to the exhibition from within Greece were the Acropolis Museum, Athens; Agora Museum, Athens; Archaeological Museum, Eleusis; Archaeological Museum, Samos; Kerameikos Museum, Athens and the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Other institutional lenders were the British Museum, London ; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Musée du Louvre, Paris ; Musei Capitolini e Monumenti Communali, Rome, Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek, Munich and Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung. The great number of lending institutions and particularly those from Greece was heralded as a coup when the exhibition was announced, though there were serious misgivings within the archaeological community and leftwing political groups in Greece. The number of loans from European museums was used as a selling point by the institutions marketing the exhibition and even by reviewers who were otherwise hostile to the exhibition. For example, in a review for The New York Times, Holland Cotter wrote that ‘the one truly democratic feature of The Greek Miracle is that it brings this work to viewers who may never be able to hop on a plane to Europe.' (Cotter 1993).

One of the objects lent that caused most controversy in Greece was slab XXXI from the North Frieze of the Parthenon, which was housed in the Acropolis Museum, Athens. The controversy over the international loan of this frieze block was due to the dispute between the Greek government and the British Museum over the legality – and the ethics – of the acquisition of the sculptures from the Parthenon and elsewhere on the Acropolis by Lord Elgin in the 1800s, as well as the British Museum's acquisition and continued retention of the ‘Elgin Collection'. The Parthenon sculptures have long been considered the artistic exemplars of Periclean Athens at the height of democracy and imperial power as well as key examples of Greek art in the ‘high classical' style (for example, Stewart 1990:150). The Parthenon sculptures owned by the British Museum were conspicuous by their absence as the legality of their retention may be threatened legally if they left Britain – as in fact happened in a loan of nineteenth-century aboriginal bark drawings from the British Museum to a major exhibition at the Victoria Museum in Melbourne, Australia in 2004. Jerry Theodorou, reviewing the exhibition for Minerva, commented that the furore created would be ‘totally out of place in the context of a birthday party for Greek democracy' (Theodorou 1992:27). Arguably the debate around the issue would be totally in context for the values and celebration of Greek democracy. One of the legacies of this exhibition was the renewed campaign for the restitution of the 'Elgin collection' from London to Athens.

Although there were a great deal of museums involved in lending objects, the number of objects in the exhibition was fairly small. Only 34 antiquities were on display at The Greek Miracle in Washington in total. This was partly due to the decision to just exhibit original objects from fifth-century Greece rather than Roman copies of original Greek sculptures such as, for example, the copy of Harmodious and Aristogeiton on display at the Archaeological Museum in Naples. The then Director of the National Gallery of Art, Earl A. Powell III and the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello wrote in the foreword to the catalogue of the exhibition:

While a more complete story of fifth-century art could be told be including later Roman copies of lost originals, Roman copies do not convey the subtlety and magnificence of the of the Greek prototypes; above all, they lack that inner life we sense in the original works.(Powell and de Montebello 1992:10)

This emphasis on the authenticity of the sculptures in both aesthetic and ideological terms is not new. It dates back to the first display of the sculptures from the Parthenon and elsewhere on the Athenian Acropolis in London in the 1800s (and arguably to the writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann before that). However, this emphasis is important for this exhibition as it presents classical art developing at the same time as and being influenced by the development of democracy. Therefore copies would not hold the ‘inner life' of the political and philosophical character of Athenian Greeks from the Fifth Century BCE. Despite this emphasis, some of the sculptures on display were not in fact from classical Athens but from elsewhere in Greece, such as the metope from the Temple of Zeus in Olympia in the Peloponnese. Arguable the combination of archaeological locations did not matter since artists travelled across classical Greece in search of commissions and so there would have been an exchange of creative techniques and ideas – though this point is not made in the exhibition catalogue. The two directors stress the importance of ‘Greek prototypes' as they were the prototypes for the traditions of later western art.

Objects

The objects displayed in The Greek Miracle exhibition are fully listed in the catalogue. It is worth drawing attention to some of the key objects exhibited and considering why they are so significant to the story of art and democracy narrated through the exhibition. These objects also contributed to the critical reception of the exhibition in reviews and analysis.

Number 1 in the catalogue and the first object seen on entering the exhibition, being displayed in its own vestibule, was the marble ‘Statue of Youth: Kouros' dating from 530-520 BCE. This kouros had been found in the Sanctuary of Apollo on Mount Ptoön in Boeotia and is now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. The sculpture was used in the exhibition to represent the late Archaic style of Greek art and to signify similar kouroi found on the Acropolis and elsewhere in Greece from that time. Kouroi are freestanding sculptures of young men – the feminine form is korai – who were possibly used as votive offerings. It also illustrated the ‘increasingly naturalistic way' of representing the human body and the ‘developed musculature and vigorous energy of the figure place it close to the end of the century' (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:79). This kouros had previously been displayed in the exhibition The Human Figure in Early Greek Art in 1988-89, where it was displayed towards the end of the exhibition and was singled out for showing a ‘notable change' from earlier sculpture in the ‘treatment of the head' (Despina Picopoulou-Tsolaki, in Sweeney, Curry and Tzedakis 1988:148). In this way the two exhibitions are connected, The Greek Miracle begins where The Human Figure finishes. Number 1 in the catalogue and the first object seen on entering the exhibition, being displayed in its own vestibule, was the marble ‘Statue of Youth: Kouros' dating from 530-520 BCE. This kouros had been found in the Sanctuary of Apollo on Mount Ptoön in Boeotia and is now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. The sculpture was used in the exhibition to represent the late Archaic style of Greek art and to signify similar kouroi found on the Acropolis and elsewhere in Greece from that time. Kouroi are freestanding sculptures of young men – the feminine form is korai – who were possibly used as votive offerings. It also illustrated the ‘increasingly naturalistic way' of representing the human body and the ‘developed musculature and vigorous energy of the figure place it close to the end of the century' (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:79). This kouros had previously been displayed in the exhibition The Human Figure in Early Greek Art in 1988-89, where it was displayed towards the end of the exhibition and was singled out for showing a ‘notable change' from earlier sculpture in the ‘treatment of the head' (Despina Picopoulou-Tsolaki, in Sweeney, Curry and Tzedakis 1988:148). In this way the two exhibitions are connected, The Greek Miracle begins where The Human Figure finishes.

The star of the show was undoubtedly catalogue number 5, the marble ‘Statue of a Youth: The Kritios Boy' (c. 500-480 BCE), which had been found (in parts) on the Athenian Acropolis and is now in the Acropolis Museum, Athens. The sculpture ‘marks a dramatic break from the canon' and was positioned behind the earlier Kouros in the exhibition at Washington DC so that the change in the more naturalistic depiction of body can be clearly seen (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992: 86 and Wills 1992:47). This use of comparison between the earlier and later sculptures was a common motif in art historical analyses of Greek art. In 1959 E. H. Gombrich used a kouros from 600 BCE (Apollo of Tenea) and one from about 500 BCE (Apollo of Piombino) to contrast with the Kritios Boy from c.480 BCE in ‘Reflections on the Greek Revolution' in Art and Illusion [Illustration from E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion (1960), p. 100]. Gombrich commented that the Kritios Boy breaks ‘the symmetry' of the tense posture of earlier kouroi ‘so that life seems to enter the marble' (Gombrich 1960:100). J. J. Pollitt, who contributes an essay to The Greek Miracle catalogue, similarly contrasts an early kouros with the Kritios Boy in his book Art and Experience in Classical Greece, which was first published in 1972 (Pollitt 1972:15). Even if the Kritios Boy is not contrasted to earlier Greek sculptures, the sculpture plays a part in any survey of Greek art, such as John Boardman's Greek Art, and acts as an example of the early classical style of Greek sculpture (Boardman 1996). The Kritios Boy is purportedly made by a sculptor called Kritios, though this attribution is due to the fact that the head has similarities with the head of Harmodius from the Tyrannicide group by Kritios and Nesiotes. However tenuous the connection between sculptor and sculpture, a named piece fits more readily into the western art tradition of emphasising the individual creator of an art work. Perhaps most significantly, the artistic innovations seen in the Kritios Boy are taken to physically embody the developing democratic politics of Athens, as J. J. Pollitt comments in an essay in the exhibition catalogue: The star of the show was undoubtedly catalogue number 5, the marble ‘Statue of a Youth: The Kritios Boy' (c. 500-480 BCE), which had been found (in parts) on the Athenian Acropolis and is now in the Acropolis Museum, Athens. The sculpture ‘marks a dramatic break from the canon' and was positioned behind the earlier Kouros in the exhibition at Washington DC so that the change in the more naturalistic depiction of body can be clearly seen (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992: 86 and Wills 1992:47). This use of comparison between the earlier and later sculptures was a common motif in art historical analyses of Greek art. In 1959 E. H. Gombrich used a kouros from 600 BCE (Apollo of Tenea) and one from about 500 BCE (Apollo of Piombino) to contrast with the Kritios Boy from c.480 BCE in ‘Reflections on the Greek Revolution' in Art and Illusion [Illustration from E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion (1960), p. 100]. Gombrich commented that the Kritios Boy breaks ‘the symmetry' of the tense posture of earlier kouroi ‘so that life seems to enter the marble' (Gombrich 1960:100). J. J. Pollitt, who contributes an essay to The Greek Miracle catalogue, similarly contrasts an early kouros with the Kritios Boy in his book Art and Experience in Classical Greece, which was first published in 1972 (Pollitt 1972:15). Even if the Kritios Boy is not contrasted to earlier Greek sculptures, the sculpture plays a part in any survey of Greek art, such as John Boardman's Greek Art, and acts as an example of the early classical style of Greek sculpture (Boardman 1996). The Kritios Boy is purportedly made by a sculptor called Kritios, though this attribution is due to the fact that the head has similarities with the head of Harmodius from the Tyrannicide group by Kritios and Nesiotes. However tenuous the connection between sculptor and sculpture, a named piece fits more readily into the western art tradition of emphasising the individual creator of an art work. Perhaps most significantly, the artistic innovations seen in the Kritios Boy are taken to physically embody the developing democratic politics of Athens, as J. J. Pollitt comments in an essay in the exhibition catalogue:

Critics have seen this figure as perhaps the first sculptural image designed to express the new sense of individual responsibility that grew out of the Kleisthenean reforms and the Persian challenge. (Pollitt 1992:35)

In this way, it is inferred that artistic developments in Athens reflect political changes and the growth of democracy. Curiously, no mention is made of the possible erotic significance of this sculpted adolescent kouros, nor of its iconography in the body politics of Athens. The Kritios Boy embodied the ‘values' of the exhibition and was used in the marketing of the exhibition and was often the key image reproduced or referred to in reviews.

Catalogue number 9 ‘Herakles Receiving the Golden Apples of the Hesperides' dating from c.460 BCE is another sculpture that reflects the stylistic changes and expressions of the early classical style. The metope comprising the three figures of Herakles, Athene and Atlas is from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and is presented as an example of architectural sculpture. This metope is one of several sculptures which do not come from democratic Athens but is included in the exhibition nevertheless. Arguably, the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and the art work belong to a different function in Greek art and archaeology from that of classical Athens, as well as a very different political climate (Stewart 1990:143). Catalogue number 9 ‘Herakles Receiving the Golden Apples of the Hesperides' dating from c.460 BCE is another sculpture that reflects the stylistic changes and expressions of the early classical style. The metope comprising the three figures of Herakles, Athene and Atlas is from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and is presented as an example of architectural sculpture. This metope is one of several sculptures which do not come from democratic Athens but is included in the exhibition nevertheless. Arguably, the Temple of Zeus at Olympia and the art work belong to a different function in Greek art and archaeology from that of classical Athens, as well as a very different political climate (Stewart 1990:143).

Catalogue Number 10 the bronze ‘Head of a Youth or God: The Chatsworth Apollo' dating from 460-450 BCE is an example of one of several heads of sculptures displayed in The Greek Miracle. The bodies of the sculptures may have been lost but heads are used to depict the ‘severe' facial expression of the early classical style and the change from the serene archaic smile. This head is also the only object lent by the British Museum and was originally found in Cyprus in 1836, becoming part of the ‘Chatsworth collection' before being acquired by the museum (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:101). The inclusion of a loan from the British Museum is significant given the objects that were not loaned from the museum: namely the sculptures from the Elgin Collection. Catalogue Number 10 the bronze ‘Head of a Youth or God: The Chatsworth Apollo' dating from 460-450 BCE is an example of one of several heads of sculptures displayed in The Greek Miracle. The bodies of the sculptures may have been lost but heads are used to depict the ‘severe' facial expression of the early classical style and the change from the serene archaic smile. This head is also the only object lent by the British Museum and was originally found in Cyprus in 1836, becoming part of the ‘Chatsworth collection' before being acquired by the museum (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:101). The inclusion of a loan from the British Museum is significant given the objects that were not loaned from the museum: namely the sculptures from the Elgin Collection.

Catalogue number 11 ‘Statue of a Horse' dating from 470-460 BCE was one of many small bronzes loaned to the exhibition by various museums, in this case from Olympia. This horse was commented on by reviewers of the exhibition and pictures of it reprinted. The catalogue entry also stresses its similarity to the depiction of horses on the Parthenon frieze and the visitor could compare this bronze to the frieze displayed later in the exhibition (ibid.:104) Catalogue number 11 ‘Statue of a Horse' dating from 470-460 BCE was one of many small bronzes loaned to the exhibition by various museums, in this case from Olympia. This horse was commented on by reviewers of the exhibition and pictures of it reprinted. The catalogue entry also stresses its similarity to the depiction of horses on the Parthenon frieze and the visitor could compare this bronze to the frieze displayed later in the exhibition (ibid.:104)

Smaller bronzes also stood in for larger sculptures that had often been lost but were known about through Roman reproductions or extant bronzes that could not be loaned to The Greek Miracle.

Catalogue number 20, the bronze ‘Statuette of Zeus' dating from c.450 BCE was loaned from the Louvre and depicts Zeus in the act of hurling a thunderbolt. This statuette is representative of the large bronze Zeus or Poseidon in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which was supposed to be in the exhibition but then was not allowed to be lent ‘possibly for conservation reasons' (Theodorou 1992:26). In this case the bronze statuette stands in for a well known sculpture. Catalogue number 20, the bronze ‘Statuette of Zeus' dating from c.450 BCE was loaned from the Louvre and depicts Zeus in the act of hurling a thunderbolt. This statuette is representative of the large bronze Zeus or Poseidon in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which was supposed to be in the exhibition but then was not allowed to be lent ‘possibly for conservation reasons' (Theodorou 1992:26). In this case the bronze statuette stands in for a well known sculpture.

Catalogue number 22 ‘Calvary from the Parthenon Frieze' dating from 442-438 BCE is one of the most significant objects in the exhibition because it is a frieze block (Slab XXXI from the North Frieze) from the Parthenon and dates from the height of Periclean democracy. The Parthenon frieze is important in the story of democracy in Athens not just due to the dating of the pieces to the refurbishment of the Acropolis orchestrated by Pericles after the democratic reforms of the 460s BCE. It is also an example of an art work, whose creation was overseen by Pheidias and is traditionally positioned within the ‘high classical' style. The frieze is also considered by many scholars to depict the important Athenian festival of the Panathenian, when a new peplos was presented to the goddess Athene and the whole city took part in a procession to the Acropolis. [1] The frieze, therefore, is not only an example of the high style of classical art composed at the height of Athenian democracy but is also believed to represent the city of Athens and its citizens. Catalogue number 22 ‘Calvary from the Parthenon Frieze' dating from 442-438 BCE is one of the most significant objects in the exhibition because it is a frieze block (Slab XXXI from the North Frieze) from the Parthenon and dates from the height of Periclean democracy. The Parthenon frieze is important in the story of democracy in Athens not just due to the dating of the pieces to the refurbishment of the Acropolis orchestrated by Pericles after the democratic reforms of the 460s BCE. It is also an example of an art work, whose creation was overseen by Pheidias and is traditionally positioned within the ‘high classical' style. The frieze is also considered by many scholars to depict the important Athenian festival of the Panathenian, when a new peplos was presented to the goddess Athene and the whole city took part in a procession to the Acropolis. [1] The frieze, therefore, is not only an example of the high style of classical art composed at the height of Athenian democracy but is also believed to represent the city of Athens and its citizens.

Catalogue number 24 ‘Nike Unbinding Her Sandal' dating to c. 410 BCE from the frieze of the small unfinished Nike temple on the Athenian Acropolis is an exuberant study of drapery and the human body. It is often taken to be an exemplar of the end of the high classical style and the move to late classical style and the catalogue entry recognises that its style ‘had a long lasting impact Greek sculptors' (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:132). The frieze also dates from the end of the fifth century and the Peloponnesian War and so represents a historic turning point in Greek politics and society. Catalogue number 24 ‘Nike Unbinding Her Sandal' dating to c. 410 BCE from the frieze of the small unfinished Nike temple on the Athenian Acropolis is an exuberant study of drapery and the human body. It is often taken to be an exemplar of the end of the high classical style and the move to late classical style and the catalogue entry recognises that its style ‘had a long lasting impact Greek sculptors' (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:132). The frieze also dates from the end of the fifth century and the Peloponnesian War and so represents a historic turning point in Greek politics and society.

The exhibition displayed many grave stelei due to their artistic rendition and as a way of depicting individuals from ancient Greece.

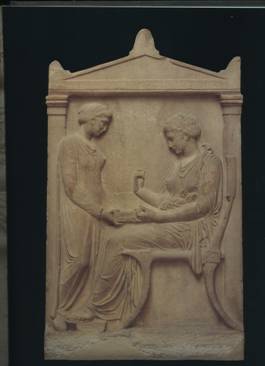

Catalogue number 28 ‘Grave Stele of a Little Girl' dating from 450-440 BCE is a rare example of an object from an American museum, namely the Metropolitan Museum of Art . Although more objects from the Met were added in the display in the Met itself at New York. This attracted some comment from American reviewers as the Met's collection was said to ‘hold its own', though Beryl Barr-Sharrar commented that ‘it is to be hoped' that American museums would collect more works from fifth century Greece (Barr-Sharrar 1993a:18). The depiction of a child on a stele from Paros adds a sense of individual portraiture of ancient Greeks to the exhibition, which is continued in ‘Grave Stele of Hegeso' (catalogue number 33) Catalogue number 28 ‘Grave Stele of a Little Girl' dating from 450-440 BCE is a rare example of an object from an American museum, namely the Metropolitan Museum of Art . Although more objects from the Met were added in the display in the Met itself at New York. This attracted some comment from American reviewers as the Met's collection was said to ‘hold its own', though Beryl Barr-Sharrar commented that ‘it is to be hoped' that American museums would collect more works from fifth century Greece (Barr-Sharrar 1993a:18). The depiction of a child on a stele from Paros adds a sense of individual portraiture of ancient Greeks to the exhibition, which is continued in ‘Grave Stele of Hegeso' (catalogue number 33)  dating from c. 400 BCE. dating from c. 400 BCE.

The inclusion of the name of the female central figure and that of her father (Proxenos) within the lintel gives a personal history to this object as well as being an example of an Athenian stele that originally stood in the Kerameikos Cemetery in Athens. Although the name of the woman and her father is known, it would only be by being a daughter, wife and mother that she would play a part in Athenian democracy – though the catalogue does not mention this. Hegeso is also pictured being attended by a female slave and again no mention is made of the identity of this person or of their role in democratic Athens.

The emphasis in The Greek Miracle is on sculpture, whether in marble or bronze. There were no red or black figure vases listed in the exhibition catalogue, which seems a curious omission given the red figure technique was developed in the early fifth century in Athens. Red-figure vase painting is arguably more uniquely Athenian and representative of Athenian society than sculpture. Neither were there any smaller items, other than the bronzes. The objects alone signify that the exhibition had a traditional art historical setting with little archaeological context or social history. This could be because of The Birth of Democracy exhibition, which was scheduled to open only a month after the closure of The Greek Miracle and was curated by the same person, as well as the fact that both venues were art galleries rather than archaeological museums.

History Heroes and Texts

There were no portrait busts in The Greek Miracle. Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy. The Fifth Century BC. The emphasis was not on the personalities of the period but on the art created, whether temple architecture, free standing figures or funerary memorials. Some attention is paid to the practice of known sculptors working in the period, such as Euenor whose signature is on the ‘Statue of Athena' (catalogue number 7) in the exhibition or Pheidias who directed the sculptural work on the Parthenon. The work of these sculptors and others are used to provide some evidence for the development of Greek art in the fifth century BCE. However, given little is known about these artists and many of the objects have no recorded creator, the story of Greek art is told through the objects themselves and information about their rendition.

The fact that there were no portrait busts of Pericles, or other architects of Athenian democracy, in the exhibition meant that key individuals were discussed within the context of the exhibition (on the text panels or in the catalogue) but were not used to drive the narrative of the exhibition forward. The main emphasis was on Kleisthenes and his constitutional reforms in Athens in 507/8 BCE, which is to be expected given that is the date taken to be the founding of democracy in Athens and the reason for the 2,500th anniversary. Both J. J. Pollitt's and Olga Tzachou-Alexandri's essays on art and politics and Athenian democracy in the catalogue respectively mention Themistokles, Ephialtes and Pericles (Pollitt 1992). They also make use of Thucydides' Histories and Aristotles' Politics as well as the works on the constitution attributed to Aristotle and ‘The Old Oligarch', as evidence for the development of Athenian democracy. Danill I. Iakov's essay ‘The Contribution of Greek Drama to the Political Life of Athens' in the catalogue stresses the importance of drama to and as evidence for Athenian democracy and the four key playwrights Aischylos, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes are listed (Iakov 1992:65-68). Key events are more important than individuals in The Greek Miracle and these are: the reforms of Kleisthenes in 508/7 BCE; the battle of Marathon in 490 BCE; the battles against the Persians of Thermopylea and Salamis in 480 BCE; the defeat of the Persians at Plataia in 479 BCE; the founding of the Delian League in the 470s; the democratic reforms of Pericles in the 460s and 450s; the Peloponnesian War in 431-404 BCE and the defeat of Athens by the Spartans.

Curation of The Greek Miracle

The guest curator of The Greek Miracle was Diana Buitron-Oliver (1946-2002), a classical archaeologist and lecturer at Georgetown University in Washington DC. Buitron-Oliver had previously curated The Human Figure in Early Greek Art at the National Gallery of Art in 1988 (January 31 – June 12 1988). Buitron-Oliver clearly had experience at organising and interpreting a large exhibition filled by international loans and at working in partnership with museum professionals and archaeologists in Greece. Buitron-Oliver also co-curated with John McK. Camp II the exhibition The Birth of Democracy: An Exhibition Celebrating the 2,500th Anniversary of Democracy, which was held at the National Archives in Washington DC from June – December 1993.

Any exhibition requires a team of people to input their knowledge. The vast number of people from within the National Gallery of Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as those from Greek museums and the Ministry of Culture and other international lenders, thanked in ‘Foreword' and the ‘Acknowledgements' give a sense of the scale of the exhibition (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:10-12 and 14-16). The exhibition was officially organised by the National Gallery of Art in collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Ministry of Culture of the Government of Greece. Buitron-Oliver was assisted by a range of people. The Greek co-ordinator was Katerina Romiopoulou, Director of Antiquities for the Ministry of Culture of Greece. From within the National Gallery of Art, members of the exhibitions department, the corporate sponsorship team, the information office, the publications department, the conservation laboratory and designers all worked together on the exhibition. The education department wrote the accompanying exhibition brochure (not the catalogue), the wall texts and the audiovisual accompaniment. Carlos A. Picon (curator in charge of the Greek and Roman Department at the Met) co-ordinated the exhibition in New York.

The high profile nature of the exhibition also meant the Directors of the National Gallery of Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art, Earl. A. Powell III and Philippe de Montebello respectively were heavily involved, as were directors of leading Greek museums, such as the Director of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens Dr Olga Tzachou-Alexandri and the Director of the Acropolis Museum Dr Peter G. Calligas. In fact, the exhibition had been backed by the former Director of the National Gallery of Art J. Carter Brown, who left shortly before it opened. Carter Brown was well known, if not notorious for his emphasis on blockbuster exhibitions in the 22 years he was at the National Gallery. The Prime Minister of Greece Constantin Mitsotakis and the deputy Tzannis Tzannetakis are thanked, as are the Greek ambassador to the United States Christos Zacharakis and the United States ambassador to Greece Michael Sothiros. Members of all lending institutions are thanked and there is an additional list of contributors and people who gave assistance to the exhibition catalogue. The journalist and writer Nicholas Gage, who wrote the ‘Introduction' to the catalogue, is thanked for his energy in guiding the project (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:11).

Interpretation, Location, space and display

Exhibitions are ephemeral. They may in part reflect the collecting practice, aesthetics of display and transition of knowledge of in a particular museum institution but the temporary nature of an exhibition means that the exact way in which these different processes are displayed can never be recaptured. A great deal of information about exhibition can be found in a consideration of the objects that were chosen for display and so exhibition catalogues are very useful. The scholarly content and information in catalogues also gives us an idea of the theme and focus of an exhibition. The venue in which the exhibition is located will also impart meaning. The Greek Miracle was displayed at two public art museums – the National Gallery of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art – which both have an object-orientated approach to displays; that is a focus on an aesthetic or classification approach in their presentation of objects. [2] In this case the focus was very much an aesthetic one, though The Greek Miracle also attempted to present a sculptural time line of Greek art from 500 to 400 BCE in a manner that could be described as classificatory. Michael Shanks and Christopher Tilley have described the way archaeological artefacts are presented as aesthetic objects in museums:

The artefact is displayed in splendid remoteness from the prosaic, from the exigencies of everyday life. The concrete and historically viable practice of production and consumption is collapsed into the ‘aesthetic', an isolatable and universal human experience. Instead of abstract objectivity, the abstract experience of the aesthetic becomes the exchange value of the artefact (Shanks and Tiley 1992:73).

It is clear from the nature of the objects chosen, the reviews of the exhibition (considered later) and the dominant mode of display in the two venues that The Greek Miracle utilised this aesthetic object orientated approach. Such an approach goes some way in how the objects were interpreted – in this case presenting them as art historical ‘masterpieces'.

Interpretation in museums produces meaning. Hugh A. D. Spencer provides a useful definition of interpretation, describing it as ‘the intended and effective communication of other messages and experiences to visitors – through exhibitions and other public programs.' (Spencer 2007:201). There are various tools of interpretation, beyond the method of display used. The orientation, style and design, exhibition guide, text panels (of all varieties), audio-visual elements, catalogue and a programme of activities relating to an exhibition are all part of its interpretation. The Greek Miracle had an audiovisual presentation on fifth-century Greece shown in an adjacent space, which was narrated by Christopher Plummer (a prestigious actor) as well as tours, lectures and a symposium. A children's guide to the exhibition was also produced alongside the catalogue. There are limitations to finding out about the various public programmes, the style, text panels and audiovisual presentation so long after an exhibition, though information about them is probably held in the archives of the National Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum. A more in depth museological study would consult these archives if possible. However, reviews of the exhibition can give some information about the presentation and content of the exhibition.

Architecturally the National Gallery of Art was suited to hosting the exhibition as it is a grand neo-classical building, designed by John Russell Pope and built in the late 1930s. Although the exhibition was actually displayed in the upper level of the mezzanine in the East Building extension (presumably in the ‘special exhibition gallery space') and this space was constructed in the late 1970s. The huge building project was overseen by the former director of the National Gallery, J. Carter Brown and the building was designed by I. M. Pei. After opening on 1 June 1978, this flamboyant museum extension has influenced architectural style for new museums and extensions since. The National Gallery is also located at the heart of Washington DC on the Mall, the grand road on which numerous museums are situated that leads to the Washington Monument.

The archaic kouros was the first object seen on entering The Greek Miracle. Situated in its own vestibule, Gary Wills commented that the influence of Andrew Stewart's book of plates (Greek Sculpture Vol. 2 1990)* showing the outline of the archaic kouroi loosening into the early classicism of the Kritios Boy can be seen in the exhibition:

All these are commonplaces of art history, but they become alive with a special force when one sees the clearly lit Kritios Boy ‘unveiled' behind the more dimly illuminated kouros – by moving to the left or the right of the kouros, one can look through either of two windows into the next room, where the Kritios Boy is placed in the center of our vision. It is a clever way of accomplishing what Stewart did by means of his composite drawing (Wills 1992:48).

The lighting of the objects is dramatic and evidently drew on natural light as well as spots. In the National Gallery of Art natural light from above illuminated the sculptures in the Upper Level of the Mezzanine in the East Building.

The sculptures were displayed at eye-level. The decision to display the sculptures – particularly those from temple friezes – at eye-level bothered Wills who had had the fortune to lie under the frieze block from Olympia when the exhibition was in build and saw the difference in viewing the sculptural relief from eye-level as the Heracles ‘looked down on me as I looked up'. Querying why these sculptures are displayed at eye level with Diana Buitron-Oliver, Wills finds out that Oliver considered raising the sculptures but the National Gallery did not want them displayed in this way (ibid.:49). The sculptures were also displayed at eye level in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which Beryl Barr-Sharrar considers as drawing the visitor as near as possible to the ancient artist's experience and that the sculptures are ‘best appreciated at close range' (Barr-Sharrar 1993a:20). Placing the objects at eye-level is typical of the traditional method of display in art museums, which positions all objects within a gallery as art objects, irrespective of their original function. This position also reflects the traditional vantage point of looking at these sculptures as art objects created by individual artists. In order to give the objects in the exhibition some geographical context, large photographs of the Acropolis and other sites in Athens were used as well as an 1865 photograph of excavations on the Acropolis, in which the unearthing of the torso of the Kritios Boy is recorded (Barr-Sharrar 1993a:19). Overall the consensus with regards to the display of the objects in The Greek Miracle at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC was that it was it was well presented and ‘elegant' (Richard, 1992). However, the ideological politics of the exhibition and its scholarship met with a more ambivalent view from critics and in some cases caused hostility.

The Greek Miracle moved from the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in March 1993. The main change in the exhibition at the Met was the addition of sculptures from the museum's own collection. From within the museum's own Greek and Roman department, six more original marble sculptures and four small bronze figures were added as well as three small works from private collections bringing the number of objects on display to 45 (Barr-Sharrar 1993b). Unlike the National Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum has a large Greek and Roman department and two of the museum's collection had already been included in The Greek Miracle. The Met's collection enabled them to position their own earlier kouros (600-580 BCE) at the entrance to the exhibition in the circular upper gallery of the Lehman wing in the museum (Illustration 1).

(Illustration 1) (Illustration 1)

The sculptures were again lit by natural light and, though critics were ambivalent about the ideological meaning of the exhibition, they were unanimous about its aesthetic presentation:

Visually the show is enthralling.... They have been beautifully installed in the museum's Robert Lehman Wing. The prospect of large-scale fifth-century BC marbles sculptures bathed in natural light and in view of one another across the airy courtyard is one of the must-see sights of this art season. (Cotter 1993)

The Catalogue

The Greek Miracle exhibition catalogue appears in many respects to be the same as any other exhibition catalogue with its collection of forewords, essays, acknowledgements and stunning photographs of the objects displayed. However, it is unique in beginning with ‘Statements' from the President of the United States and the Prime Minister of Greece. There can be no possible doubt about the political importance to the United States and Greece of this exhibition and the ‘2,500th ' anniversary of democracy. The Greek Prime Minister Constantin Mitosakis comments that ‘only in Athens and the United States has democracy lasted as long as two centuries on a continuing basis' and states that it is ‘fitting' that the sculptures' ‘first journey from their homeland' should be to the US (Mitsokatis 1992:6). President George Bush Snr. shares this sentiment, while making the exhibition of the sculptures from fifth century Athens on the anniversary of democracy have a global resonance. Considering the influence of the ancient Greeks on the Founding Fathers of America, Bush writes that:

Today, modern Greece stands as a valued partner in an alliance that has helped to defend and promote human rights throughout the globe while ensuring the collective security of Europe.

It is my hope that each visitor to this exhibit will gain not only a deeper appreciation of ancient Greek sculpture but also a renewed sense of gratitude for our shared democratic heritage. (Bush 1992:7)

George Bush's statement is dated July 2 1992 and he himself was about to begin fighting a presidential election in the US at that time, which he later lost to Bill Clinton. Bush's oblique references to the role of Greece in NATO and their protection of ‘security of Europe' draw attention to the allying of Greece with America in the Cold War against Communist Russia and Europe. This alliance had recently seen the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and its European allies, leaving America as the dominant global power. The ‘dawn of democracy' is used to celebrate uncritically this alliance between Greece and the US, despite the many contentious issues that make the relationship problematic, such as the US involvement in the Greek Civil War after World War Two or support for the Greek military dictatorship in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The magnitude of the exhibition is given further weight by the inclusion of a foreword by the two directors of the host venues Earl A. Powell III from the National Gallery of Art and Philippe de Montebello from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Powell and Montebello stress the importance of the image of man to Greek art and the influence on this image of political change and philosophical thought, arguing that there are ‘firm cultural grounds for seeing in the works of art a sense of measured action with full consciousness of its consequences'. (Bush 1992:7). The museum directors do not ground the exhibition within contemporary political history but rather re-direct attention to the impact of Athenian democracy on the development of Greek art 2,500 years ago and see this exhibition of fifth century figural art as representative of the traditions of western art history. Diana Buitron-Oliver continues this train of thought with her references to the eighteenth-century scholar Johann Joachim Winckelmann, often described as the ‘father of art history' and the opinions of the more recent classical art historian and archaeologist Bernard Ashmole (Buitron-Oliver et al. 1992:14). Buitron-Oliver edited the essays included in the catalogue, which were mainly contributed by members of the Greek Ministry of Culture and wrote the text for the objects. These essays were the mainstay of the catalogue and, while blandly informative, they discussed the development of Greek art within the context of Athenian democracy and glowing descriptions of Greece more generally. They comprised: ‘Athenian Democracy' by Olga Tzacou-Alexandri; ‘Architecture in Fifth-Century Greece' by Vassilis Lambrinoudakis; ‘The Human Figure in Classical Art' by Angelos Delivorrias; ‘Ancient Greek Bronze Sculpture' by Peter G. Calligas and ‘The Contribution of Greek Drama to the Political Life of Ancient Athens' by Daniil Iakov.

Two of the ‘specialist' essays are worth more comment. The prominent classical art historian and archaeologist Olga Palagia wrote a chapter entitled ‘The Development of the Classical Style in Athens in the Fifth Century'. Palagia, a lecturer at the University of Athens and author of a book The Pediments of the Parthenon in 1993, placed the sculptures from The Greek Miracle within a greater artistic context. She drew on comparisons with sculpture in Egypt and the Near East and linked the sculptures displayed in a sequential development of art from the late archaic style of the late sixth century to the burgeoning of a new style c. 400 BCE. Palagia stressed the centrality of the visual perception of the human figure in Greek art and the importance of the ‘classical moment' with the replacement of formulaic art by the ‘art of illusion'. (Palagia 1992:23). Palagia's emphasis on the ‘art of illusion' replacing formula and mythology is a neat nod to the art historian E. H. Gombrich, whose chapter ‘Reflections on the Greek Revolution' in Art and Illusion considered the centrality of the human figure in the achievement of Greek art in breaking mythical taboos to create greater mimesis in art (Gombrich 1960: 119).

Yale professor J. J. Pollitt positioned the objects from The Greek Miracle within the context of political reform and events in fifth-century Athens in his chapter ‘Art, Politics, and Thought in Classical Greece'. This chapter drew on Pollitt's influential book Art and Experience in Classical Greece, which was first published in 1972 and relates the formal development of art to political and cultural history, using literary, historical and philosophical texts from the period as evidence. Pollitt is alone in the catalogue in emphasising the importance of vase painting in influencing the development of other artistic forms and also in drawing attention to the traumatic yet liberating impact of the Persian Wars and the Greek victories at Marathon, Salamis and Plataia. Pollitt considers the political use of certain myths and their sculptural rendition, such as the labours of Heracles on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. He argues that Athens as a wealthy and imperial power could fund the building programme on the Acropolis, which was influential on artistic creation in Greece. Similarly to the treatment in his Art and Experience, Pollitt considered the Athene Nike adjusting her sandal from the Nike temple as ornamental art made for its own stake and as symbolic of the falling fortunes of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian War (Pollitt 1992:43 and Pollitt 1972:115).

The catalogue also included two essays by non-specialists. The Greek-American writer Nicholas Gage wrote the ‘Introduction' to the exhibition catalogue. Gage, while acknowledging the influence of other Mediterranean cultures on the Greeks, stressed the importance of individual freedom and the equal distribution of political rights in Athens to create a ‘Greek Miracle' in art, literature and philosophy. Nicholas Gage, born Gatzoyiannis in Greece in 1939, fled from Greece to America at the end of the Civil War between Royalists and Communists in 1949. Gage worked as an investigative reporter for The New York Times and while in charge of the Greek bureau, investigated the execution of his mother at the end of the Greek Civil War and what happened to her killers. This was published in 1983 as Eleni and was a best-seller and critically acclaimed. Eleni was turned into a film in 1985 and its anti-communist rhetoric attracted the attention of President Ronald Regan, who made a reference to it in a televised address after a summit meeting with President Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987. Gage is therefore in a unique position to comment on ancient Greek democracy and its American ‘successor' being a Greek-American, the survivor of a brutal civil war involving communists and a representative of the ‘triumph' of the US capitalist political system. As a best selling and internationally recognized author, Gage's involvement would also generate publicity for the exhibition. In his opening paragraph, Gage compares fifth-century Greek art and culture to a ‘new sun':

Its light has warned and illuminated us ever since; sometimes obscured by shadows, then bursting forth anew as it did when our own nation was created on the model of the Greek original. The vision – the classical Greek ideal – was that society functions best if all citizens are equal and free to shape their lives and share in running their state: in a word, democracy. (Gage 1992:17)

The Canadian novelist Robertson Davies completes the catalogue's essay with ‘Reflections from the Golden Age' in which he considers how Greek art had been understood in the Western world since Winckelmann in the mid-eighteenth century and how every age has invented its own Greece. Robertson considered that the best way to consider ancient Greek psychology was to consider the importance of Greek religion and mythology rather than just simply reflect the ancient Greeks as ‘ourselves in fancy dress'. (Davies 1992:72). Robertson Davis was a writer who wrote plays and essays but was best known for his novels and in the 1970s wrote fiction that drew on Jungian psychology and painted satirical portraits of small town Canada. Davies finished his essay by emphasising the importance and accessibility of Greek art over Greek literature for most people and by extension most visitors to the exhibition.

The core catalogue of The Greek Miracle is made up, as most exhibition catalogues, of beautifully shot photographs of the objects from various different angles and close ups of the sculptures. Accompanying text gives information about the provenance of the sculpture, an analysis of its importance in the history of Greek art and occasional references to contemporary literature, such as Pindar's Odes. Unlike the catalogue for The Human Figure, there are no references to further reading material. Reviewers of the exhibition universally referred to the catalogue as ‘nothing to write home about', ‘stereotypical', intellectually ‘undistinguished (and in a few instances positively xenophobic)' (Wills 1992, Richard 1992 and Cotter 1993, respectively). This in part reflected hostility to the ideological framework of the exhibition overall, the overt political message in the ‘presidential statements' and the traditional (and nationalistic) attitudes imparted in the essays of the catalogue.

Marketing and Sponsorship

The exhibition The Greek Miracle was announced at a live satellite press conference on 4 June 1992 from both the National Gallery of Art and the Zappion exhibition centre in Athens. The exchange of antiquities from Greece, ‘many of which have never been allowed to leave Greece', for paintings from the two American institutions involved was the main focus of The New York Times reporting of it the next day (Vogel 1992). An exhibition held at the National Gallery in Athens entitled From El Greco to Cezanne: Three Centuries of Masterpieces from the National Gallery of Art, Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York was comprised of 35 Old Master paintings from the Met and about 35 French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings from the National Gallery. The National Gallery in Athens had to improve its security and conservation conditions in order to secure the loan and advisers from America were sent to ensure improvements were made.

The corporate sponsor of the exhibition was announced as Philip Morris Companies Inc. Philip Morris Companies Inc is a tobacco company that also produce fast food products and beer. In their corporate report for 1992, Philip Morris list supporting The Greek Miracle exhibition in the ‘Supporting the Arts' section of their Corporate Citizenship programme.[3] Philip Morris was one of the biggest corporate sponsors of the arts in the early 1990s, particularly known for sponsoring blockbuster art exhibitions. Their sponsorship of The Greek Miracle raised questions about the ethics and politics of sponsorship, particularly within the climate of cuts to the National Endowment for the Arts, which funds public arts bodies. Restrictions on advertising by tobacco companies in America, due to awareness about the health problems caused by smoking, meant that other forms of advertisement and promotion were used by such companies. Sponsoring a major exhibition is a shift of ‘direct advertising to indirect publicity' for Philip Morris Companies Inc. (Batchen 1995). In an advert, ostensibly for The Greek Miracle, that was placed by Philip Morris Company Inc in The Washington Post on the day the exhibition opened on 22 November 1992, the bust of the Kritios Boy appeared above a long caption:

“We are all Greeks,” the poet Shelley said. Born of democracy. Invention. Philosophy. Theatre. History. Sciences. And art, born from that democracy makes us so. For out of the fifth-century Greece, modern man was given life. Now the art of the Golden Age of Greece is here, to explore, embrace and revel in. An historical event – of great importance to all of the western world – a study of man and democracy through art... Art as evolution. As mankind. As free. As all. For now, as in the age of Perikles, politics flower. History writes itself anew. Man challenges his world. Art tells the story. And we, in awe, muse over the miracle of democracy. (Requoted in Wharton 2001:54)

Underneath this text is a number for the National Gallery of Art and the dates of the exhibition and then a promotion for Philip Morris Companies ‘Sponsoring Innovation' (Illustration 2).

Illustration 2 Illustration 2

Annabel Wharton has observed that ‘with its affected syntax and rhetorical clichés, this text voices a popular understanding of the relationship that exists between modern western democracies and ancient Greek artefacts.' (Wharton 2001:54). The sponsorship of The Greek Miracle by a tobacco company offended many and was sometimes commented on in reviews. (For example Wills 1993:47). The misleading equation of ancient Athenian democracy with capitalist based ideas of freedom leads to interesting questions about the reception of ideas from the classical world in contemporary society. Questions such as how much is democracy in the modern world tied to a capitalist free market economy and how (or, indeed, does this) have any relevance for the reception of democracy and political practice in the classical world.

How the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum or the Greek Ministry of Culture advertised The Greek Miracle is hard to ascertain in retrospect, though no doubt some information would be in the relevant archives.

Statistics and Miscellaneous Information

The Greek Miracle attracted 270,075 visitors while it was at the National Gallery of Art, which was an average of 3,500 visitors a day during the exhibition. It was clearly popular and attracted more people over a shorter space of time at Washington than the earlier exhibition of Greek art The Human Figure.

The exhibition was free but tickets needed to be booked in advance via the museum or for a fee from ticketmaster at the National Gallery of Art, which is a free venue. The Metropolitan Museum charges an entry fee and entry to the exhibition was included in this charge, though timed tickets to the exhibition needed to be booked in advance.

Reviews and Critical Reaction

The Greek Miracle attracted negative critical attention, and this will be investigated shortly. However, the one thing all the reviewers agreed on was how well presented the exhibition was, as well as the spectacular quality of the art works on display. Recurring words such as awe, contemplative, expressiveness and ‘text book example' were used to describe the sculptures in the exhibition. Jerry Theodorou in Minerva gave the exhibition a glowing review and commented that in the plethora of events taking place to commemorate 2,500 years of democracy The Greek Miracle was the ‘most visually impressive' (Theodorou 1992:23). Theodorou concentrates on listing and describing the importance of the key works in the exhibition, such as the Kritios Boy, the bronze statue of Zeus and the Hegeso stele. Another positive review was by Paul Richard in The Washington Post, 22 November 1992, who positioned the sculpture historically in the context of Egyptian art as well as events in Greece. Richards made a reference to the German art historian Erwin Panofsky's point that funerary monuments are prospective or retrospective. Egyptian monuments show the dead in the afterlife at peace so they are prospective, while Greek monuments commemorate and mourn the dead with depicting events from their life (Richard 1992). Otherwise the review concentrated on art works, their mimesis and the feelings they inspired:

A new idea of beauty was born among these objects. Man-centered, serene, it fused timelessness and movement, poignancy and aplomb. It's a beauty that's endured the rise and fall of Rome, the depths of the Dark Ages and the camera as well, and still governs our ideas of bodily perfection.

To walk among these fragments, these bronzes and these marbles, is to see the ancient gods of Greece – tall, gray-eyed Athena, mighty bearded Herakles – leaving their transcendent world and entering our on. It's like the moment in the myth when Pygmalion's Galatea first begins to breathe. In the first rooms of this exhibit, Apollo comes alive. (Richard 1992)

When the exhibition opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Economist reviewed it and referred to the Greek ‘masterpieces', very much stressing the aesthetics of the classical ideal embodied in the show. The reviewer had qualms about the ‘socio-political rot' driving the exhibition but believed that the exhibition illustrated the aestheticism of the Greeks, ‘even though it is fashionable now to demean such masterpieces of western art as elitist.' (The Economist, 'Greek Miracle', 10 April 1993:102)

Two longer reviews of Met Show for two more specific arts publications (The New Criterion and Art in America) by Beryl Barr-Sharrar engage more critically with the material and the exhibition's position within a broader art historical framework. Barr-Sharrar's article for Art in America begins with Winckelmann and his belief that sculpture made at the height of classical Greece embodied the noble values of the Greeks in the eighteenth century, and then continues with a reference to the morphological evolution of sculpture as described by Brunilde Ridgway in the 1970s and 80s. Barr-Sharrar considers how the transition of the late archaic kouros evolves into the early classical and more naturalistic Kritios Boy in the exhibition and whether the idealisation of beauty was related to ‘high spiritual and mental qualities' (Barr-Sharrar 1993b). She puts these representational changes in the context of Polykleitos and his Kanon for sculpture, which is reflected in the exhibition in the bronze figurines. In Barr-Sharrar's review for The New Criterion, she draws attention to the differing perceptions of gender that are represented in the sculpture on display and points out that the Kritios Boy is ‘erotically suggestive' (Barr-Sharrar 1993a:23). Neither gender nor the erotics of sculptural representation are referenced in the exhibition catalogue, which suggests that they were not considered important by the curators. Barr-Sharrar stresses that ‘we are all heirs of Wincklemann' and the assumptions of traditional western art history in our attitudes to colour on sculpture – implying that this exhibition doeas not engage with the use of colour. Barr-Sharrar concludes with pointing out the lack of reference to the religious dimension of the demand for art in classical Greece and anthropological readings of the ancient Greek world.

Gary Wills in The New York Review of Books also draws attention to the original use of colour on sculpture and the dynamics of art commissions and Greek religion. Wills stresses the superstitious belief system of the ancient Greeks, arguing that a herm as an example of this should have been included in the exhibition. He compares The Greek Miracle with an exhibition on indigenous American art that is on show simultaneously in the Art Institute of Chicago (The Ancient Americas: Art from Sacred Landscapes), which explores more vividly the ceremony and function of art:

One gets closer to the ancient Greeks – and therefore to their art – by studying primitive cultures than by remasticating for the thousandth time the ambrosial reflections of J. J. Winckelmann. (Wills 1992:50)

Wills' main issue, however, was with the extended equation that Democracy equals ideality equals humanism equals rationalism equals naturalism equals individualism and equals Athens, as well as the Athenocentrism of this equation. The exhibition, displayed a significant number of objects from sites external to Athens and beyond Athenian control. Wills pointed out that there was more than democracy taking place in Athens and the wealth in Athens was due to its empire and not least to its use of slaves in the silver mines, but that these issues were not referred to even when a slave is depicted on the Hegeso grave stele (ibid.: 48). Wills also commented on the 'nervousness' of the Greeks in lending the antiquities and the sponsorship by a tobacco company Philip Morris Companies Inc as completing 'the impurities necessary to pull off this Greek miracle. Despite all that it is miraculous.' (ibid.: 47).

Theodorou in Minerva also mentioned the ‘nervousness' of Greek archaeologists in loaning the sculptures for an international exhibition and the conservation concerns that were raised. There were more than conservation concerns driving Greek protests about the loan – though these were important. Concerns related to nationalist and leftwing politics were also raised about this loan of antiquities to an overseas exhibition. Eleana Yalouri describes the attitude to the antiquities in Greece as being ‘part of the national body' and that members of the Archaeological Society of Athens were divided over the decision to send antiquities to The Greek Miracle exhibition. The pro-government supporters argued that the antiquities acted as ‘global ambassadors' for Greece, while those in opposition to the loans, who were generally on the left politically, considered that the national meaning of the sculptures was in danger of erosion and that through travel physical harm could come to the antiquities themselves (Yalouri 2001: 67). This issue was picked up by Michael Kimmelmann in his review for The New York Times, which commented that the Greeks were 'understandably concerned about risking through travel some of the central monuments of Western civilisation on the basis of such an intellectually meagre excuse' (Kimmelman, NYT, 22 November 1992).

The New York Times ran two reviews, one after the opening of each exhibition in Washington DC and New York. Each of these reviews was highly negative about the political agenda explicit and implicit in the exhibition, but complimentary about the display of the sculptures. In an article headed ‘Sublime Sculptures in a Dubious Setting', Michael Kimmelman reviewed the DC exhibition as an opportunity to see ‘masterworks' of Greek art and that if people concentrate on the art they will enjoy the show. However, Kimmelman had problems with the lack of up to date contemporary scholarship on Greek art or ancient Athens in the exhibition and, as he saw it, poor historical integrity. (This was an issue highlighted about the catalogue in otherwise positive reviews of The Greek Miracle, for example Paul Richard in The Washington Post described it as ‘long on generalities and short on focused scholarship', Richard 1992). His review finishes with a condemnatory broadside about the prevailing emphasis on ‘blockbuster' exhibitions in American museums:

Intellectually unambitious masterwork exhibitions like this are really about power as much as anything else, about the power of the National Gallery and the Metropolitan to act like big game trophy hunters, mounting on their walls the bounty of over nations. Audiences have become accustomed in the television age to having everything made easily available. And museums are so loathe to sully their triumphs by raising the possibility that a plane or truck carrying one of these priceless objects might actually get into an accident that even to bring up the issue of risk and responsibility, as archaeologists have done in this case, sounds alarmist. (Kimmelman, NYT, 22 November 1992)

Unspoken in Kimmelman's review is the politicising of the sculptures within an equation that equates ancient Athenian democracy and concepts of freedom with modern democracy (specifically American democracy) and liberty, though clearly his attack on the incoherence of the narrative driving the exhibition references this.

Barr-Sharrar commented that the exhibition at the Met in New York focused on the aesthetic quality of the sculptures, ‘leaving politics behind in DC' (Barr-Sharrar,1993b). The exhibition in New York was considered to be less politicised, which raises a number of questions. Was this due to the enlarged exhibition at the Met? Where there new panels around the exhibition when it changed location? Or was it simply because it was no longer in the political centre of America ? Although it is difficult to gauge, the answer is probably a combination of all three. In the review of the enlarged exhibition at the Metropolitan in The New York Times, Holland Cotter stressed the visually enthralling power of art works and the ‘international commodity exchange', but his main issue was with the lack of ‘an original thought in its handsome head':

The world renowned objects have been gathered not in the interest of new scholarship nor in an attempt to see with fresh eyes the complex society that produced them, but as a kind of travel brochure, replete with a jingoistic promotional title meant to perpetuate clichés about art and its meaning that recent art history has been trying to dislodge. (Cotter 1993)

However, the most damning review of The Greek Miracle, in New York or DC, was by renowned art historian and critic Robert Hughes in Time magazine. Hughes commented on the loans from Greece and the dangers of the objects' travel to an exhibition ‘with an utter shallowness of argument about their social and ritual meanings' and ‘practically no scholarly value' (Hughes 1993). Hughes, like the other reviewers, thought the show should not be missed by those who have not seen this art before but is dismissive about the ties between sculpture and democracy – pointing out that women and slaves did not have any political freedom – and terms it ‘political PR'. Hughes considers The Greek Miracle to be an uncritical appreciation of Greek art in the manner of Winckelmann and quotes a poem (Autumn Journal) written by Louis MacNeice in the 1930s to illustrate how this stereotypical vision of Greece has been challenged. MacNeice's poem on ‘the crooks' of Greece finishes with ‘and lastly/ I think of the slaves'. Hughes pointed out that there is no mention of the role of slaves or slavery in the exhibition, ‘as important an institution for Periclean Greece as for America's antebellum South', in the exhibition (ibid.). With this comparison, Hughes implies that there was also a lack of mention of the role of slavery in America's celebration of ‘two hundred years' of democracy. Hughes' main problem, as with other reviewers, was that there was no reference to the ritual role of religious ‘votives' or to the superstitious belief system that lay behind the construction of art works and temples. The ‘neoclassical' vision of the show did not recognise the startling colour of the sculptures or the frightening imagery of classical Greek art:

And far from rising above anxiety, classical Greek art polluted with horrors: snakes, monsters, decapitated Gorgons, all designed to ward off the terrors of the spirit world. One sometimes wonders if ancient Greece, more lurid than white, so obsessed with blood feud and inexpungible guilt, wasn't closer to modern Bosnia than to the bright world of Winckelmann. But you cannot put that kind of ‘classicism' in a museum, or relate it to democracy. (ibid.)

The Greek Miracle took place during a year full of conferences and scholarly meetings discussing democracy, ancient and modern, and in fact a symposium was held as part of the exhibition. The only immediate and direct academic response to The Greek Miracle is in the remarks made by Ian Morris and Karl Raaflaub in a volume of papers and responses from a conference at the Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington DC in September 1993. Morris and Raaflaub contended that The Greek Miracle had been taken over by the politicians at a time when ‘democracy was on every one's mind'. They pointed out that the historical stories behind The Greek Miracle were not as simple as represented in the exhibition, that there was no reference to Athenian imperialism, nor to the fact that democracy was hated by many (particularly in Greek city states outside of Athens) and also dared to ask ‘how Greek was Athens?' (Morris and Raaflaub 1998:1-2).

There is very little reference to The Greek Miracle exhibition in other academic volumes from the years of the anniversary. There are various reasons for this. The archaeological evidence rather than art historical objects, could be said to be more important for illustrating the process and practice of democracy and this was illustrated in the later The Birth of Democracy exhibition. In discussions on the nature of participatory democracy in Athens and ideas such as eleutheria (speaking or acting like a free man) or isegoria (equality) the emphasis was on textual evidence, which was not presented in the exhibition. The politically bipartisan views expressed in the exhibition, the unproblematic representation of Athenian democracy as an ideal and the overtones of Greek nationalism arguably served to estrange academics in the areas of ancient history and classical archaeology from The Greek Miracle. Coupled with this was the exhibition's remoteness from contemporary scholarship. Even if the exhibition's prime purpose was to simply to display art works from Greece, it seems clear from the reviews that analysis of the role of colour on sculpture and the function of art in religious cults and ceremonies did not play a part in the interpretation of the objects.

‘Masterpieces', ‘textbook examples' and ‘enthralling visual display' were the kind of laudatory expressions used in the press to describe The Greek Miracle. The show was considered aesthetically successful in terms of the material it displayed and its manner of presentation. Despite this, many reviewers were critical of the exhibition and even hostile to it (this is not a comprehensive survey of every review of the exhibition). However, it is likely that many smaller reviews followed the tone of the short weekend review ‘Head Over Heels in Greece' in The Washington Post, which considered The Greek Miracle a beautiful exhibition to see while in town (Burchard 1992:65). There is also the political dimension and potential partisan ‘party politics' behind the reviews. The New York Times is known for being ‘liberal' and, on the whole, a Democrat supporting paper. It is likely that it and its reviewers would be hostile to an exhibition endorsed by the incumbent Republican President George Bush, particularly at time of a general election when the economy is in a recession. There would also be concerns about the expression of Greek nationalism while a vicious and ethically divisive war was tearing Greece's Balkan neighbour Yugoslavia apart. Hughes' reference to Bosnia draws attention to the atrocities of the Serbian army and government. An important factor behind the poor reviews was also that many critics recognised that it had little to do with the work of contemporary scholarship in classics and art history and was traditional in its presentation of Greek history and art history.

Bibliography

Annual Report 920000, Philip Morris Companies Inc, 26 January 1993, on www.tobaccodocuments.org, p. 27 [last accessed 18/05/2008].

Barr-Sharrar, B. 1993a. 'The Greek Miracle : Classical Sculpture at the Met', The New Criterion Vol. II/9: 18-23.

Barr-Sharrar, B. 1993b. ‘The figure as moral construct' – exhibition of Greek sculpture at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Art in America, http://findarticles.com [last accessed 13/05/2008]. Batchen, G. 1995. ‘Where there's smoke... cigarette companies sponsoring art exhibitions', After Image, 23.

Black, G. 2005. The Engaging Museum. Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement. London: Routledge.

Boardman, J. 1996. Greek Art.London: Thames and Hudson.

Buitron-Oliver, D., et al. 1992. Exhibition Catalogue: The Greek Miracle: Classical Sculpture from the Dawn of Democracy, the Fifth Century B.C, Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art.

Burchard, H. 1992. ‘Head Over Heels in Greece', The Washington Post, Weekend, November 27:65.

Bush Snr., G. 1992. ‘Statement', in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992:7.

Cotter, H. 1993. ‘Ancient Greeks at the Met: Matter over Mind', The New York Times, March 12, http://query.nytimes.com [last accessed 29/04/2008].

Davies, R. 1992. ‘Reflections from the Golden Age' in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992: 69-76.

Gage, N. 1992. ‘Introduction' in Buitron-Oliver, 1992:17-20.

Gombrich, E. H. 1960. Art and Illusion. A Study in the psychology of pictorial representation. London: Phaidon.

‘Greek Miracles', 1993. The Economist, April 10, 327/1.

Hughes, R. 1993. ‘The Masterpiece Roadshow', Time, January 11, http://www.time.com [last accessed 29/04/2008].

Iakov, D. I. 1992. ‘The Contribution of Greek Drama to the Political Life of Athens', in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992: 65-68.

Jenkins, I. 1994. The Parthenon Frieze. London: British Museum Press.

Kimmelman, M. 1992. ‘Art View: Sublime Sculptures in a Dubious Setting', The New York Times, November 22.

Mitsokatis, C. 1992. ‘Statement', in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992:6.

Morris, I. and Raaflaub, K. 1998. ‘Introduction', in Morris and Raaflaub (eds.) 1998:1-9.

Palagia, O. 1992. ‘The Development of the Classical Style in Athens in the Fifth Century', in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992:23-30.

Picopoulou-Tsolaki, D., J. Sweeney, T. Curry and Y. Tzedakis (eds). 1998. The Human Figure in Early Greek Art. Athens and Washington DC: Greek Ministry of Culture and National Gallery of Art.

Pollitt, J. J. 1992. ‘Art, Politics and Thought in Classical Greece' in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992:31-44.

Pollitt, J. J. 1972. Art and Experience in Classical Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Powell, E. A. and P. de Montebello.1992. ‘Foreword', in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992:9-12.

Richard, P. 1992. ‘Beauty and the Greeks: At the National Gallery, Timeless Sculpture from 500 BC', The Washington Post, G.01, November 22 1992.

Shanks, M. and C. Tiley. 1992. Re-constructing Archaeology: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

Spencer, H. A. D. 2007. ‘Interpretative Planning and the Media of Museum Learning', in Lord, 2007.

Stewart, A. 1990. Greek Sculpture. An Exploration. Volume1: Text. London, Yale University Press.

Strauss, B. S. 1998. ‘Genealogy, Ideology and Society in Democratic Athens', Morris and Raaflaub (eds.) 1998:141-54.

Theodorou, J. 1992. ‘The Greek Miracle: Fifth Century Greek Sculpture visits the United States', Minerva, 3/6: 23-27.

Tzachou-Alexandri, O. 1992. ‘Athenian Democracy', in Buitron-Oliver et al., 1992:45-50.

Vogel, C. 1992. ‘The Art Market', The New York Times, June 5, http://topics.nytimes.com/ [accessed 19/05/2008].

Wharton, A.J. 2001. Building the Cold War. Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wills, G. 1992. ‘Athena's Magic', New York Review of Books, 39, December 17 1992:47-51.

Yalouri, E. 2001. The Acropolis. Global Fame, Local Claim. Oxford: Berg.

Endnotes

[1] This view has been put forward by many scholars, but Ian Jenkins (a curator at the British Museum) is perhaps the best proponent of this theory – see Jenkins, 1994).

[2] Black, 2005:275. Also, for more on the ‘civilizing rituals' and the cultural politics implicit in visiting a public art gallery, see Duncan 1995, particularly 48-71.

[3] Annual Report 920000, Philip Morris Companies Inc, 26 January 1993, on www.tobaccodocuments.org, p. 27 [accessed 18/05/2008].

|